Insight article

Plato on storytelling

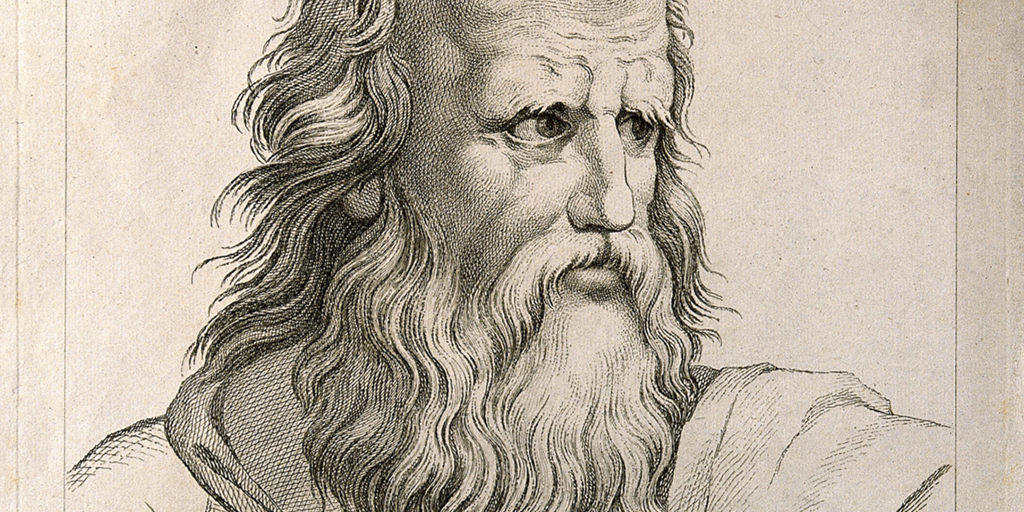

Of all the philosophers in the Western tradition, Plato is amongst the most celebrated. One twentieth-century academic characterized the rest of Western philosophy as ‘a series of footnotes to Plato’.

Socrates’ erstwhile pupil is also credited with the invention of the university, and his most famous work, The Republic, is – amongst other things – an educator’s handbook. For Plato, the education of a state’s Guardians – its warrior class – was of fundamental importance. In devising his ideal state in The Republic, education is the first issue he considers.

And what is the first subject Plato addresses on the Guardians’ curriculum?

Storytelling.

No, really.

The Republic is written as a series of dialogues between Socrates and various other men whose only real task is to agree with Socrates or provide the answer he has remorselessly steered them towards. This is how the education bit gets going:

‘What kind of education shall we give them then? We shall find it difficult to improve on the time-honoured distinction between the physical training we give to the body and the education we give to the mind and character.

True.

And we shall begin by educating mind and character, shall we not?

Of course.

In this education you would include stories, would you not?

Yes.’

Isn’t that wonderful? First thing the great philosopher puts on the ideal syllabus: stories. But not just any stories. Plato turns a little dark at this point:

‘Then it seems that our first business is to supervise the production of stories, and choose only those we think suitable, and reject the rest. We shall persuade mothers and nurses to tell our chosen stories to their children, and by means of them to mould their minds and characters which are more important than their bodies. The greater part of the stories current today we shall have to reject’.

Goodness. Talk about the nanny state. What kind of objectionable stories does he have in mind? Mostly legends of gods and heroes, such as those in Homer’s Iliad. For example:

‘Nor can we consent to regard Achilles as so grasping that he took Agamemnon’s presents, or refused to give up Hector’s body unless he was paid a ransom […] We cannot, in fact, have our citizens believe that Achilles […] was in such a state of inner confusion that he combined in himself the two contrary maladies of ungenerous meanness about money and excessive arrogance to gods and men’.

But it wasn’t only the mythical stuff that worried him:

‘Poets and storytellers are in error in matters of the greatest human importance. They have said that unjust men are often happy, and just men wretched, that wrongdoing pays if you can avoid being found out, and that justice is what is good for someone else but is to your own disadvantage. We must forbid them to say this sort of thing, and require their poems and stories to have quite the opposite moral’.

Some readers take a very dim view of all this. Plato stands accused of fascist censorship and revisionism. But as storytellers I think we can draw a more positive message from Plato’s intense interest in our craft: he wanted to control storytelling because he understood how very powerful it could be in shaping culture, character and behaviour.

This is what he has to say about those fictional stories that don’t always set their semi-divine heroes in the best light:

‘Moreover such lies are positively harmful. For those who hear them will be lenient towards their own shortcomings if they believe that this sort of thing is and was always done by the relatives of the gods. If we want our prospective Guardians to believe that quarrelsomeness is one of the worst evils, we must certainly not let them be told the story of the Battle of the Giants or embroider it on robes. We can admit to our state no stories about Hera being tied up by her son, or Hephaestus being flung out of Heaven by his father for trying to help his mother when she was getting a beating’.

That last one has a very modern resonance, doesn’t it? “What are these brutal video games doing to our children’s minds?” we hear today. What does it mean that Grand Theft Auto glorifies violence and rape? Is there a connection between gun violence on screen and in real life?

But it wasn’t just vice that disturbed Plato; he wanted stories to set the right example to his city guardians. And because good men were supposed to be self-sufficient and not dependent on property or loved ones, they definitely shouldn’t be seen to grieve over their loss:

‘Then we should be quite right to cut out from our poetry lamentations by famous men. We can give them to the less reputable women characters or to the bad men, so that those whom we say we are bringing up as Guardians of our state will be ashamed to imitate them’.

Real men don’t cry. Your story had better say as much if you want a job in the ideal state.

So far, Plato has outlawed plenty of story angles. What would he like to see in their place? There aren’t many clues in The Republic, but here’s one:

‘When a poet tells or a dramatist presents tales of endurance against odds by famous men, then we must give him an audience’.

It’s not only behaviours that interest Plato. He also recognises the importance of a positive vision or destination in stories. Again, he makes his point rather negatively:

‘And will anyone who believes in terrors in the afterlife be without fear of death, and prefer death in battle to defeat in slavery?

No.

It looks, then, as if we shall have to control storytellers on this topic too. We must ask the poets to stop giving their present gloomy account of the afterlife […] and make them speak more favourably of it.

We must get rid, too, of all those horrifying and frightening names in the underworld – the Rivers of Wailing and Gloom, and the ghosts and corpses, and all other things of this kind whose very names are enough to make everyone who hears them shudder. They may do well enough for other purposes; but we are afraid that the thrill of terror they cause will make our Guardians more nervous and less tough than they should be’.

Of course, we don’t know what Plato really believed the afterlife to be like, but it seems he was prepared to stretch the truth, as he saw it, in the interests of the state:

‘It will be for the rulers of our city, then, if anyone, to use falsehood in dealing with citizen or enemy for the good of the State; no one else must do so’.

These days, we might encourage a CEO to be optimistic, rather than actually deceitful, in concluding her narrative with a really positive vision of the future.

Plato understood that the more compelling a story, the more powerful its effect. For those stories that conveyed the wrong moral message, the more compelling they were the more urgently they must be banned:

‘It is not that they are bad poetry or are not popular; indeed the better they are as poetry the more unsuitable they are for the ears of children or men’.

So, in conclusion, one of the greatest philosophers of all time believed storytelling was fundamental to preparing Guardians (leaders) to perform their role in the ideal state (company). He recognised the key role stories play in shaping cultures, promoting desirable behaviours and inspiring action.

But lest we get too filled with a sense of our own importance, Plato is quick to put us storytellers in our place:

‘My dear Adeimantus, you and I are not engaged on writing stories, but on founding a state. And the founders of a state, though they must know the type of story the poet must produce, and reject any that do not conform to that type, need not write them themselves’.

We should be grateful: if founders/clients went around writing their own stories, where would we be?