Insight article

The mnemonics of progress

Here at The Storytellers, we like to visualise our stories. A narrative with a beginning, middle and end that has been visually represented, bringing words and images together in a synthesised manner, exerts so much more power than words alone. By showing the emotional trajectory of a story as an image that connects the key moments of that journey, the art and science of storytelling comes to life.

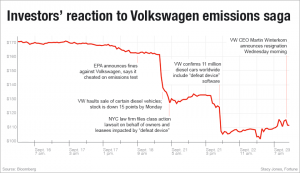

Which brings us to the seemingly bland looking image above: a simple stock price chart. This chart was not written by any one person, and it’s not particularly aesthetically pleasing. But as a story, it is utterly absorbing. It viscerally tells the tale of leadership gone wrong, sacrificed values, disastrous decision-making – and above all, a faulty, incomplete concept of progress that brought Volkswagen, one of the world’s biggest companies, to its knees.

Much has been said on the VW emissions scandal regarding the idea of bringing values to life, that values cannot simply be words on a piece of paper. But I think it’s more than this. The challenge that Volkswagen failed to live up to is one that we continually see our clients wrestle with: how do we move forward without losing sight and sense who we are?

Fundamentally, it’s a question that leads to a deeper, even more slippery question: what does ‘progress’ really mean?

As you can imagine, there are countless ways to answer this: for you, maybe it’s technological – digital transformation is clearly changing the world we live in, and for the most part, for the better. How technology is changing our lives is one of the defining features of our era, and we can visibly see advancement in this respect. It’s obviously progress.

It may be scientific – indeed, our entire academic system is built on the notion that by pooling our efforts and resources, as a world we will be able to comprehend the systems and rules that underpin our entire existence. Our discoveries in the various scientific disciplines arguably inform every single other area of human thought, and this is a tradition that goes back for centuries – for some, the idea of progress is indelibly connected with scientific thought and exploration.

It could also be social – #metoo, black lives matter, transgender rights… arguably the story of the 21st century so far is of different sets of people rising up around the world to claim their place as equals. The liberation of all peoples has never been far from the broader idea of what human progress really constitutes, and this trend has shown no signs of slowing down in our era either.

Whatever your personal passions and inclinations, behind these different themes of progress that inform and shape the society in which we live and work, there is a more fundamental distinction to draw.

Most prevailing ideas of progress are fundamentally forward or cumulative in nature. So for example, ‘technological progress’ presupposes that we will know more, be more capable, have greater resources tomorrow than we do today. Technological progress, as we tacitly understand it, probably would not involve replacing cloud storage with floppy disks or Uber with horse-drawn carriages.

However, it is clear that there is a growing sense in society that progress does not always entail a never-ending drive into the new and unknown. Indeed, when one considers the idea of environmental progress, it is evident that this kind of progress has many conservative aspects. Establishing colonies on Mars excepted, environmental progress is largely concerned with protecting the balance of our ecosystem; a balance that is threatened by other areas of human progress. Not losing the rainforests, ice caps and millions of threatened species would surely represent ‘progress’ in the environmental sense.

In the political sense of progress too, it’s striking to note that the two great shockwaves of our time, Brexit and Donald Trump, were both predicated and sold on the notion and appeal of in fact going back to another time when things were better. When it comes to the idea of political progress, we are seeing striking similarities across the Western world of people wanting to return to a better time, to a status quo that is already known and that people are familiar with. Even supporters of these movements would find it a stretch to classify this kind of progress as cumulative in the way that scientific or technological progress are.

In this sense then, there are two fundamental types of progress: one which is concerned with reaching ever greater heights, of voyaging bravely into the unknown – and one that is concerned with not losing what we already have, of retaining things that we have determined to be worthy.

It’s not so much that one is right and one is wrong – it’s that in order to truly succeed and respond well to change, one must be prepared to synthesise these two concepts of progress. And it is here where we find the crux of the Volkswagen tragedy. To put it simply, the leadership of Volkswagen prized financial progress and growth above retaining the values that had made them one of the most loved and respected brands in the world. The result, a modern tragedy, is that Volkswagen’s executive team have spectacularly failed in the very thing that they set out to achieve.

So as a business, how does one go about finding this delicate balance between forging into the new and unknown, while retaining the values and identity that made a brand successful and respected by customers in the first place?

It is here where a strategic narrative is uniquely well-placed to dialectically fuse the old and the new, the future that we want sewn together with the past that we wish to retain. A strategic narrative necessarily incorporates the past, the present and the future. By agreeing the right elements for each of these parts, we take control over what we need to retain, and what we need to boldly build towards. It’s a behavioural contract and compass.

In this way, strategic narratives are a kind of mnemonic that we can all be held accountable to – by squaring the past with the future, we should find that there is nothing in our actions and behaviours today that are somehow outside of what we are saying is the way forward.

The illustrative stories that colour, enrich and bring true meaning to these strategic narratives are the lifeblood of a strategic narrative. Did any of the Volkswagen executives ever share anecdotes and stories that brought to life their value statement at the time – “Sustainable, collaborative, and responsible thinking underlies everything that we do”? It’s hard to imagine that any major, sincere efforts were made in this area. Conversely, it’s easy to imagine meetings and conversations that centred on how financial gains could be made, at any cost.

It sounds simple (and most likely a tad optimistic in terms of the intentions of the Volkswagen executive team), but I suspect the main problem at the heart of the emissions scandal was a lack of ability to see the whole picture at once. When we consider Hanlon’s razor (“Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity”), and what Hannah Arendt called ‘the banality of evil’, we see that the 20th century and the early years of the 21st century continue to teach the same lesson: that until humans are given shorthand systems for behavioural judgment that simultaneously incorporate the past, an envisioned future, and a code for acting in the present, it is highly likely that how we choose to behave on a day to day basis will be desperately at odds with the desired destinations that, surprisingly often, we all share.

Strategic narratives and how we consciously connect the living, illustrative stories that happen around us are the solution to this problem. They comprise what can be called ‘mnemonics of progress’ – shortcut ways to hold in our hands the parts of our past that are worth bringing into the future, together with the bright new tomorrow that we bravely aspire to. It’s a heuristic that enables all of us, as individuals, as communities, as companies, to make sure that as we move into an ever more exciting, challenging and dynamic future, that we prevent what we have learned along the way, as a species, from being lost.